The most powerful unrecognised human force yet to boost business productivity and transformation is now the socially internet literate, connected, post-Facebook workplace mind, organised for purpose, and here’s a straightforward how-to for putting it to work across your business to transform your business’s collective intellect into a force for improved ROI your rivals will struggle to match

What follows beneath:

- Your greatest ROI challenge is most likely one you’ve not yet seen or begun to work on

- How quickly will the intelligence of your rival outwit you, and what will you do about it?

- What is the post-Facebook connected intellect?

- Knowledge must not be wasted just because leaders don’t know where it exists

- With a reliable process, you can build new value from what your people know

- Follow basic rules for publishable writing if you want to be understood

- Ask a better question

- Transform responses into meaningful reports

- Build excellence through experience and repetition

- Create usable deliverables for management

- Why the needed evolution of usable connected intelligence may not happen naturally in many businesses

- Diversity creates both strength and complexity

- And then there are the politics of digital transformation

- Where does “social internet literacy” come from?

- About me

- Testimonial: A former client working for the nation’s largest bank says this of the value of my work

Simply by getting curious and understanding how to ask better questions of the tacit knowledge of those working within them, businesses may learn much to grow ROI on their most precious intelligence, that of their connected intellects.

Your greatest ROI challenge is most likely one you’ve not yet seen or begun to work on

We may still be in the earliest years of the internet, but just as in your own company, every mind in every rival business with which you compete is now better connected than ever before.

And the degree of precision with which those minds can be steered in unison to drill down into, pick apart and articulate any workplace’s problems and challenges is unprecedented.

This makes it only a matter of time before someone sets a new standard for the ways in which they learn to organise the intelligence, tools and knowledge currently hidden within their business.

Thus, at the emerging knowledge frontier, when every business uses the cloud, the next killer app is unlikely to be a physical technology.

Much more disruptively, it will likely be the ease with which that rival can reach into its connected intellect in search of its solutions.

How quickly will the intelligence of your rival outwit you, and what will you do about it?

Because it will learn quickly how to work with and grow that collective intelligence, the rival able to capture most effectively as a platform technology the power of the connected intellect in its business will become the most formidable of competitors.

And, as its human component is the only ingredient that can imagine, ask and answer every critical question any business has about itself, its management team will quickly learn how to apply this method of working to every question of survival and advance it has in its company.

As Albert Einstein is quoted: “If I had only one hour to save the world, I would spend fifty-five minutes defining the problem, and only five minutes finding the solution,” it will quickly find that truly understanding the problem may be more important than its answer.

No matter what other machines it uses, the intelligence bound up in any organisation also remains the only reliable tool it has for its own rigorous self-examination and continuous improvement, because that is where its experience lies.

Yet, despite this prospect being so close and obvious, while so near to the surface and accessible in ways never before exploited, the potency of our most precious and precise, connected human resource – imagination, insight, experience and the capacity to articulate, learn, iterate, improvise and develop – remains under-used in most businesses.

This capacity is rarely accurately symbolised by rank or qualification. Rampant tacit knowledge – what we don’t know we know, and the perspective we have learnt simply through our individual experience of living and working – is everywhere, and like a virus, it recognises no borders and no authority.

No company can be managed to make itself more productive or optimally to boost its ROI when its true intellectual capacity remains unexamined and invisible.

If a business can’t, or chooses not to see it, it can’t get better usage from knowledge it already has, and in which it has already, almost certainly unknowingly, invested.

Unused knowledge is a drag on any business, when it knows neither what it knows, nor whether it is drawing on its best minds in framing and answering its internal questions.

The situation becomes worse when it is relying simply on the few best positioned and adept at playing either their authority or its politics.

And, as long as they remain out of sight, unexplored and unknown, your company’s individual and collective insights can tell you nothing about how you will make your business smarter.

They can tell you nothing about who you should hire next, or how you can configure your workplace around the intelligence it must attract, retain, nurture, grow and protect and reward, and what for.

So, against such reality, do you know for a fact that your strategy is based on fact, or is it possible your competitor has a resource and a way of thinking as a team that gives it a better way of thinking and planning?

And, if it has a better way of working, have you thought through how that will affect your ROI? How well will you know how to counter that strategy?

That resource to put to work is already present at every desk within your business.

What is the post-Facebook connected intellect?

Previously, it used to be hard, if not impossible, to capture and transform into usable information the knowledge and insights of those across an organisation.

Yet, as our use of and familiarity with using the social internet grows, we have reached an age of unprecedented opportunity in making the best use of intelligence across the web-age business.

Although it is still a force unrecognised, unexamined and therefore unorganised in most organisations, through near-ubiquitous familiarity with Facebook and others, we’ve now arrived at “peak social internet literacy.”

This entirely naturally occurring capacity’s practical applications are also easily demonstrated, as we have reached the point at which every employee in every business knows how to use social media to write online, upload and share material and to make comments about those items uploaded by others.

And when such communications are in writing and captured by the mirroring, private, internal Facebook-like or networked, document-sharing technologies now available within every business, workplace knowledge, insight and learning that was once out of reach is no longer beyond management’s grasp.

Through the precise data it can drill down on, it also has access to a bottomless, renewable resource – an inexhaustible source for possible business and customer experience (CX)-improving investigation – whose creativity may be limited only by its imagination in what it asks for.

That knowledge and insight can now be applied to identifying and finding new ideas to address the problems and challenges in whichever business or society managers work.

The better and more usably they bring order to its content, the more quickly they can advance their transformations to the detriment of their rivals, and the more readily each can determine the way it transforms its literacy into fully fledged, organised workplace social internet productivity.

The professional challenge now lies in inquiring, making sense of and feeding back to any group with diverse opinions what its members know and can contribute to understanding and overcoming its challenges.

This is not overly complicated, but a straightforward task of reporting and editing, as used in the mainstream media which we are all familiar with and use every day.

Knowledge must not be wasted just because leaders don’t know where it exists

In a battle in which all the players have comparable tools, this process can put you in the driving seat to be able to work reliably with your company’s individual and collective insights to tell you what you need to know about how to make your business smarter.

When you can capture what you know, it can help you discover who it should hire next, and how you can configure your workplace around the intelligence it must attract, retain, nurture, grow and protect and reward.

The cost for leaders of not knowing and being unable to investigate what knowledge and intelligence their business possesses, is to choose to live in a bygone management era in which it remains unable to spell out what expertise it really needs.

Without active investigation, the path to their company’s most potent and rigorous collective thinking and problem-solving capabilities will never be revealed.

To be unaware of the potential of the intellect within their businesses makes it hard to take advantage of diverse views which can, through deliberate investigation, be brought to their attention, made visible, articulate and read, making its power harder still to manage.

The point is that there is knowledge you don’t know about that you don’t want to miss.

Its cost is to have to rely only on what we know of the few with which we surround ourselves, and to run a company forever held hostage by the intellectual limitations of those few best positioned, or those most adept at playing on either their authority or its politics.

When you draw only on the filtered understandings of the few rather than checking against the imagination and experience and knowledge-sharing capabilities of the many, yours is a weakened organisation.

With a reliable process, you can build new value from what your people know

Until it is harnessed, the idea of capturing a workplace’s knowledge sounds potentially chaotic, but it is no different to that faced by news organisations reporting on the world every day.

To counter such pressure, the important feature of the process I describe beneath is that it is completely neutral, timeless, established, as watertight as it can be, and everyone is familiar with its result, because it is how they have learned.

Our solution isn’t rocket science, but it is proven by centuries of learning and practice by others. It is less about storytelling than consistent story building: think weekly television drama, rather than movie.

Clearly, you could just interview everyone in your workplace to find out what they think, but while it might give you insights, it’s clearly not the best use of anyone’s time if you don’t get what you need at the time you need it, or because what you want to know doesn’t come to the interviewee’s mind at the time you talk to them.

It would also yield less, because what you want to do to spark creativity is to encourage the clash of perspectives that will throw up unexpected lines of enquiry.

At a practical level, there are also many people who know how to execute the process I describe, even if they are unfamiliar with the thinking of business knowledge management, or unfamiliar with the use of the technologies in question.

Whatever the purpose of the exercise, its goal is to report back to those involved and needing the information in a consistent, reliable fashion, such that the managers using it to make and check their decisions can drill down into this resource to keep on refining their approach to getting from it what they need.

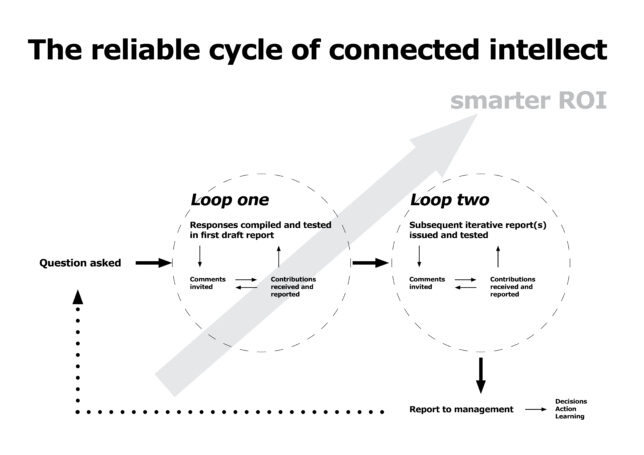

We also base this on a parallel principle of “double-loop” learning. Double-loop learning entails the modification of goals or decision-making rules in the light of experience. The first loop uses the goals or decision-making rules, the second loop enables their modification.

As described in Wikipedia, “Double-loop learning recognises that the way a problem is defined and solved can be a source of the problem. This type of learning can be useful in organisational learning since it can drive creativity and innovation, going beyond adapting to change to anticipating or being ahead of change.”

In our process, we use the first loop to understand what is known or believed, and the second loop to adjust and tighten our interrogation.

Follow basic rules for publishable writing, if you wish to be understood

In professional media production, rule number one is that every writer needs a second reader, if, at minimum, to check facts and to ensure what is written can be understood.

At the most fundamental level, this ensures that what hits the page is what the writer intended.

Naturally, this is critical if that content is meant to propel shared understanding, learning and the development of intellectual growth across your workplace.

Unchecked, imprecisely written and random material is of no help to anyone, and is a waste of everyone’s time.

The next fundamental, and perhaps the major task, is to ask questions whose responses, when reported back to the audience, advance the knowledge of the reader.

Writers work with “commissioning” editors – those who decide what the audience will actually see and how it is to be presented – to decide what must be written and what the content of those pieces must contain in order to achieve this.

The job of the reporter is then to interview those with that knowledge in accordance with those instructions.

Although the process isn’t identical when reporting the knowledge, insights and capabilities of those who hold them back to their audience within a business, it is as close as to make little practical difference.

The goal is still to make sense that achieves the reader’s goal, and to minimise problems of comprehension.

Generally speaking, what the reader most needs to know is what must grab their attention on first encountering what is reported.

So, if we want quality out, we need to put the safeguards that ensure the quality of what goes in, too.

As such, first, we must make explicit what we intend to achieve and to communicate it simply.

This rule is always the same, whatever the medium, whether it be a web site, podcast, newspaper, magazine, even a textbook.

Thinking ahead about what will stimulate it will always deliver the fastest learning.

Ask a better question

When we ask our question of a “crowd,” we must make it unambiguous, framing what we wish to see in the responses we are soliciting.

Again, we provide links and access to the available supporting resources we know of to assist those who will respond.

We must provide a deadline for submission, taking into consideration the availability of those from whom we most wish to receive contributions, as well as the schedule to which we must keep to generate reports for the leaders who commission a specific study.

The question may then be distributed via email, and/or via whichever collaborative technology we are using.

Whether their answers are to be made public when submitted, or kept private, respondents are steered via a link to make their contributions in a shareable document.

Transform responses into meaningful reports

The first wave of responses is then gathered, read and reviewed.

Ambiguous responses are checked and verified with their respective authors to ensure that what is contributed is what the writer intended, or corrected to make it so.

Then, when sense is made of them, these answers are compiled, edited and summarised in a preliminary report.

This first document is held up for further examination, as it is at this point that contributors first become aware of what others have written, which may spark other new thoughts, realisations or insights.

This report is then published in the collaborative, shared technology medium, inviting scrutiny and comment to elicit the further questions its unfinished form raises.

In it, attention may be drawn to certain answers, or parts thereof, which may hold promise, and on which the “commissioning” manager – the one deciding what is to be asked – most wants subsequent focus.

This process is repeated and these questions are incorporated into further iterations of this report until management is satisfied it has the information it needs to make decisions.

This creates the platform from which to move on to the next questions arising, based on what management has learned and how this influences what you need to know next.

Build excellence through experience and repetition

Through repetition of this process, this mechanism will reveal and report on the knowledge hidden within your organisation – and who has it – to give your leaders a new tool to work with.

Its cumulative effect will be to deliver, and to enable detailed investigation of, the collective learning that can help to build both the enhanced organisational sensitivity to its constantly shifting environment, and through this, its improved resilience.

It may be focused to frame better problem statements and to enhance the customer experience (CX).

Then, as a leader, you can learn how regularly to dive into and report on what is known in your business, such that you can discuss it, direct the search for further knowledge and steer its growth, you can repeatedly align those who have it better with its purpose and learn much faster how to turn this into advantage.

Create usable deliverables for management

If I were to work with you, by drilling down on the resulting comments, and working with your nominated executive to ensure management’s objectives are met, I would then edit and present a “final” report.

With you, I would amplify important findings to detail your recommendations and possible courses of action, such that these too may be checked for oversights, if necessary.

As a basic safeguard, at every step, this work must be conducted in concert with the leader or manager who commissions the work and wants the answers, to ensure it is always consistent with the business’s objectives.

Generally speaking, the more minds and perspectives engaged on this task, and the more precise the instructions given to them to feed into this learning, the more reliable will be the outcome.

And in this, we would specify a process that ensures the repeated production of plain English content that everyone can learn from, search successfully and build on will be as seamless, invisible and painless as possible for all to use and participate in.

This has almost nothing to do with technology, as it is all about getting the organisation thinking about, and focused on, its future.

But, if powerful ideas are to be communicated effectively, it makes the ability to communicate and build simply in writing that everyone can understand and work with one of the most important skills any organisation must develop.

Why the needed evolution of usable connected intelligence may not happen naturally in many businesses

We all understand more quickly, and learn faster, when knowledge is written and presented to us for that purpose.

Making complete sense and drawing our attention first, without distraction, to what is most important is critical if we want to get the most from the knowledge across a business.

So the ability to summarise and make sense of what is received from those contributing is essential, and the process I describe addresses this.

If the practice of finding out and articulating what goes on in the minds of others in a crowd, or across a workplace – imposing order on chaos – looks messy, it is.

For those who have never worked in media, and who have no idea of how content is managed, it may be hard even to imagine its steps independently, without being shown.

But, this is simply a process of starting with raw material that at each step is refined sufficiently until it is fit to be married with other similarly tidied material and put before an audience.

Even in media, whose contributors are mainly professional journalists, the quality of input can be highly variable, as those who can capture and communicate a story from source are not always those best able to present it to readers without others – editors – intervening in that process between them and that audience.

Against this reality, experience tells me that if it is not core to their business, many organisations simply struggle with content management.

And if its production is not familiar territory, this will certainly be the case when the information to be communicated is important and has to be managed at speed.

Diversity creates both strength and complexity

One inevitability is that across your business, while their intelligence, their ideas and suggestions may be good, the quality of its team members’ writing abilities will be uneven.

For a start, not everyone has the same gift, comfort with or care for written expression. Many people write poorly, don’t like doing it, or record information in ways that may be imprecise and unsuited to use by others.

We can also predict that without proper guidance, or checking, not all contributors will be as diligent about the consistency with which they tag, reference and index their own contributions.

Yet, effective indexing and search are really important to the learning experience by providing for ease of consumption, continuity of thought, attention and understanding for users.

Unless the right information is available and can be found consistently by applying a similar set of rules that benefit every search, learning will be inconsistent and undependable.

Poor quality documentation will deter readers, and knowledge that isn’t organised with a plan from the outset is very much harder to learn from later. (It is also much harder to want to use.)

Compounding this, most managers are too busy anyway. And where they can avoid it, many will want to have to read as little as possible, and without assistance, the burden of simply having to read too many raw social inputs may be precisely the deterrent they need to avoid doing so.

And, as they won’t wish to read or make sense of the contributions of everyone, their demand for clarity, brevity and precision will grow in line with the volume of contributions and number and diversity of participants.

As such, our purpose is to accelerate the business’s learning by bringing to it clear referential structure, plain English and sense-making in a system that is as seamless, invisible and painless as possible for all participants.

And then there are the politics of digital transformation

If they have no prior editorial media experience, even feeling confident about recruiting the right person to manage this initiative may prove a challenge.

Many businesses also continue to operate on management models that are past their prime in adapting to the realities of the competing post-industrial enterprises emerging in the age of connected intellect.

These businesses’ underpinning enterprise logic, and that of industrial capitalism, was originally built on structural foundations of bureaucracy and functional hierarchy.

Based on military precedent, the traditional leadership model for business became that of command and control.

Under this model, power resided with the board and chief executive and devolved downwards through the senior executives and their reporting managers.

It filtered down through the hierarchy to the lowest rungs of the organisational structure, with those at the coal-face charged with interacting with the market, with customers, suppliers and rivals, typically being excluded from decision making and strategy setting.

Against this view of the world, in hierarchical organisations, for those armed with it, the need to retain and lock down management control, can present a more powerful need and entrenched mental model than even the requirement that they produce profitable results.

Moreover, the change it is imposed to counter is not just quicker but also unpredictable and discontinuous, as we can see from the incursions made by new and hitherto unimagined digital business disruptors – Amazon, Google, Facebook, Airbnb, Uber, and so on.

Yet, even against such obvious discontinuities in the progress of industries, in established organisational cultures, in denial of the need to change, standard enterprise logic remains organised to reproduce itself at all costs.

Some executives will aim to protect their salaried self-interest through hierarchical status and position, and by adopting risk-averse and conservative positions and practices.

Where they exercise it, the primary source of effective resistance to change by managers remains the functional hierarchical structure, even when it may no longer make profit-generating, shareholder value-maximising commercial sense to do so.

The consequence is that structural and cultural inhibition of change persists in many organisations.

It is by adhering to established processes, so often undiscussed and beyond discussion, that even when they proclaim themselves to be changing, organisations defy the need for necessary root and branch adaptation to patent emerging circumstance.

Even when the world itself is transforming dramatically beyond the walls of the business, managerial articulation of change may remain rhetorical only.

In many organisations, such entrenched enterprise logic has become so deeply taken for granted that it is no longer visible.

And thus, when shared mental models of “how the world works” become embedded, and without curiosity being exercised and with orthodoxies remaining unchallenged, neither managers nor workforces are likely to question assumptions they no longer see.

This is even worse for external investors and owners who, at arm’s length, often see even less.

To begin unpicking this through the methods I advocate, contact me at graham@shiroarchitects.com or on 0416 171724.

Where does “social internet literacy” come from?

Of course, I can’t claim to have “created” social internet literacy any more than anyone else can claim to have invented reading, writing, typing or listening (and, granted, others may refer to this latest emergent human-productivity capacity differently elsewhere – I just haven’t found it). However, to the best of my knowledge, and unlikely as it sounds, even to me, because of my long-standing fascination with workplace social technology-driven organisational learning, I believe I may be among the first to have identified and articulated its presence as a pervasive, potent, largely under-realised and increasingly valuable management resource.

About me

Some writers may be driven to write fiction and others poetry. And, as much as I’d like to be a great novelist or an accomplished screenwriter, I have to accept that I am not made that way.

As much as I may enjoy writing, investigating and publishing, my greater inclinations are to edit and bring sense and order to what is thought up and/or written by others to make it readable and usable as a force for learning.

I am most interested in using what I can do to dig into what a company’s workplace knows and can learn to stimulate new thinking, new creativity, new business models and paths to new revenues.

To this end, as a working journalist, by getting myself appropriately educated, I’ve qualified myself to make my special discipline the discovery and internal reporting of workplace knowledge with its growth as my aim.

My understanding of the communication potential of revealing and making sense of what is known within businesses results from my being a former journalist and sub-editor – a key fact-checking, sense-making and quality control editorial role in all professional media – on the pages of The Australian Financial Review newspaper group in Sydney. That makes me an extremely picky proof-reader.

My sensitivity to the need for internet-driven digital-age organisations to learn and develop is, in turn, based on my own study and interest in the management of technology-driven organisational learning.

It is inspired by my MBA (Technology) from the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia, as that qualification focuses on creating and managing the businesses of the future, addressing changes driven by advances in digital and networked technology.

Besides my extensive media experience, I have also put in editorial time at the corporate social workplace coalface, as I subsequently also worked, using the relevant workplace social technologies, at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia at its Sydney headquarters.

At the CBA, my daily work involved using Atlassian’s Confluence wiki – a prime workplace social technology – to make sense of and turn into usable technical documentation the contributions of a diverse range of workplace contributors on a deep digital transformation project in its 200-strong software development team.

Because, while there, I learnt a lot more about how to do it better, I am chasing an opportunity that perhaps few others have yet seen. And in writing this up, I may be at risk of creating new competitors, but there is more than enough work to be done, and until AI is sufficiently advanced, the purpose-focused collective, creative, connected human mind remains the best resource we have.

For our society to advance in every way, we must bring new sense to the undeclared, tacit knowledge of businesses as a platform for their future learning and transformation, using the best internal communication tools ever invented for the purpose.

Again, contact me at graham@shiroarchitects.com or on 0416 171724.

Testimonial: A former client working for the nation's largest bank says this of the value of my work

“At CBA, Graham was tasked with building a curated knowledge base for a critical and complex project the bank was undertaking. I served as Graham’s boss during this period and have seen Graham use this project experience, combined with his MBA learning, to evolve a new understanding about how organisations can build ‘corporate memory’ and embed learning processes to better guide leadership insights.

“Based on the many conversations I have had with Graham since, I have seen the passion and knowledge Graham brings to the topic of workplace knowledge capture and organisational learning, grow and mature such that Graham is now an authority on the topic.

“Effective digital learning is an essential capability to acquire for any organisation hoping to have a prosperous future.”

Brian Davis, technology innovator, founder Software Symphony and senior software architect at the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.